Kenya is edging toward another round of external borrowing, with top officials confirming fresh negotiations for more IMF loans even after the state embarked on selling shares in parastatals to ease the tightening fiscal space.

With public debt now standing at a staggering Ksh11.8 trillion and revenue increasingly swallowed by repayments, the country finds itself cornered between dwindling financing options and a stalled economy.

The IMF’s engagement, which had slowed for months, is now back on the table, signaling a deeper financial strain than the government publicly admits.

Kenya Seeks More IMF Loans While Debt Burden Escalates

Kenya’s renewed push for more IMF loans was confirmed by Central Bank Governor Kamau Thugge during a post-MPC briefing in Nairobi. He revealed that IMF staff will land in the country in January to advance discussions on a new lending programme, months after the previous Ksh465 billion arrangement expired in April.

Thugge noted that Kenya already remains in active engagement with the Fund, with the government pushing for a new funded programme that could inject urgently needed relief into a fiscally overstretched system. But this request is unfolding at a moment when the state is simultaneously touting divestment of public enterprises, securitisation of revenue streams, and promises of cutting reliance on external borrowing.

Despite these policy shifts, the government appears unable to escape its most immediate reality: Kenya needs cash, fast—and the IMF remains one of the few doors still open.

New Programme Talks Intensify Despite Disagreements

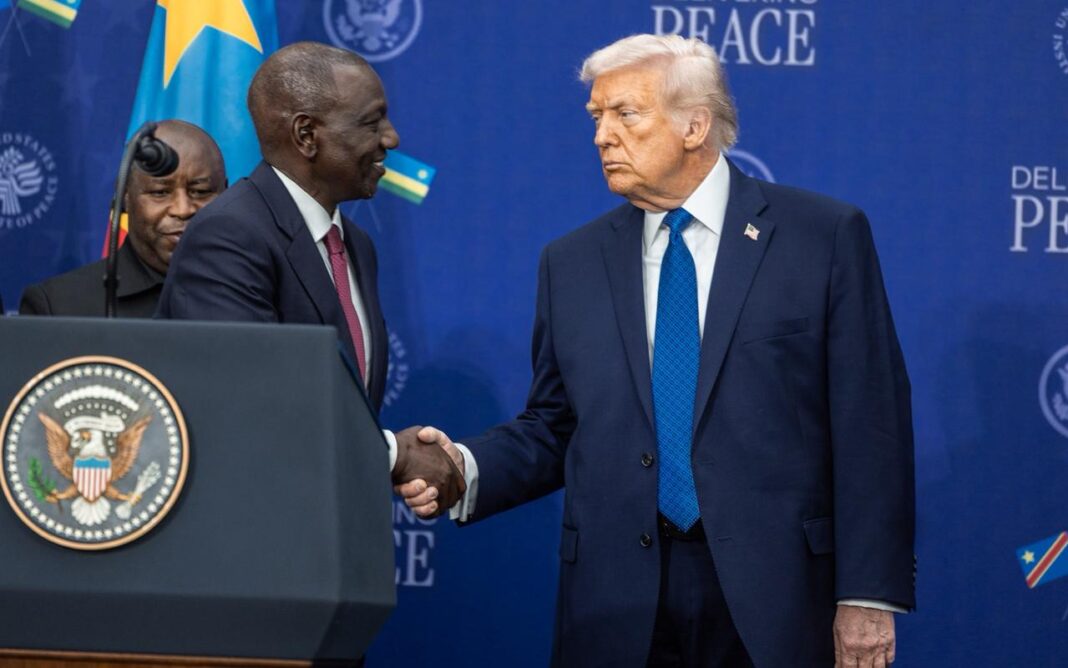

Negotiations for more IMF loans have dragged since April due to disagreements over how Kenya classifies securitised loans. The issue has become a sticking point in technical meetings, slowing progress even though President William Ruto himself has met IMF officials multiple times, including during his December trip to Washington.

The stalemate raises deeper questions about Kenya’s fiscal transparency and the sustainability of its new appetite for securitisation. While the state plans to sell stakes in parastatals and securitise certain revenues to unlock cash, the IMF’s hesitation shows that lenders are increasingly wary of opaque accounting methods.

What is clear is that Kenya’s engagement with the IMF is no longer driven by long-term reform strategy alone. It is now an urgent lifeline to plug immediate holes in a budget stretched beyond capacity.

Government Shifts Tone on Borrowing and Taxes

Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi publicly admitted what analysts have warned for years: Kenya can no longer rely on borrowing or aggressive taxation to finance grand infrastructure projects. Debt repayments already consume nearly half of all revenue, leaving shrinking room for development.

Mbadi argued that shifting viable projects to specialised commercial entities will spare taxpayers from the ballooning fiscal burden. But even with this policy change, the state continues to chase more IMF loans, signalling that restructuring alone cannot stabilise the country’s deteriorating financial position.

President Ruto has repeatedly promised that Kenya will eliminate external borrowing for development projects within 10 to 20 years. Yet the numbers tell a different story—a nation increasingly dependent on the IMF despite public declarations of future self-reliance.

Kenya Now Among Top Global IMF Debtors

The push for more IMF loans comes at a time when Kenya already ranks among the world’s top 10 IMF borrowers. According to the latest IMF data, Kenya owes SDR 2.95 billion (about Ksh519.8 billion), placing it seventh globally.

Only six countries carry more debt to the Fund: Argentina, Ukraine, Ecuador, Egypt, Pakistan, and Côte d’Ivoire. In Africa, Kenya ranks third, behind Egypt and Côte d’Ivoire, and ahead of major economies like Angola, Ghana, and Ethiopia.

This ranking underscores how deeply Kenya has leaned on the IMF in recent years, even though the political rhetoric suggests a desire to move away from external dependence.

The contradiction between public messaging and fiscal reality is now impossible to ignore. Kenya is heading back to Washington for more IMF loans, not because it wants to but because it has run out of alternatives.